References:

Manning, William. "Sheppard Frere Obituary." The Guardian, 10 Mar. 2015. Web. 3 May 2015.

Accessed From JSTOR:

Sheppard Frere and Grace Simpson

Vol. 1, (1970) , pp. 83-113

Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman

Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/525834

Article Review: The Roman Theatre at Canterbury

Sheppard Frere is the author of the academic

article. In 1945, Mr. Frere was awarded with the position as director of the

rescue excavations at Canterbury. Canterbury had been highly focused by the

German Luftwaffe during World War II, as a result many areas lay in rubble.

Sheppard Frere was responsible for archaeology excavations in the area before

any rebuilding took place in the area. Frere created an in depth sketch of the different

archaeology components of the entire city. Sheppard published his results

extensively over thirty years. Later in 1966, he became a professor of the

archaeology of the Roman Empire at Oxford University.

The article title focuses around the Roman theatre

that is located at Canterbury, England. Frere divided the article into two

major components: Description of the Site

and Stratification. Both major

components are broken down into smaller sections. The first part, Description of the Site, is divided

into: Period I Theatre, Period 2 Theatre, Destruction of the Theatre and Other

Surviving Portions of Theatre. The

second part, Stratification, is

broken into different sections discussing objects discovered within the theatre

and its surroundings. Before Frere begins his analysis of the Roman

theatre he explains how most research done at the site was done after World War

II. Sheppard admits that discoveries were made during 1868 by the city

engineer, James Pilbrow, but no detailed excavations were done. The article is

based mostly on facts and observations done while excavating. Occasionally, Frere theorized in his article about what might have caused the final demolition of the theatre or the use of a specific components within the structure. These theories are rare, Sheppard mostly takes an objective stance and communicates only facts that have been uncovered and agreed upon by professionals.

Sheppard Frere’s work is written in a fairly straightforward

manner, but has certain technical terms. Unfortunately, the definition of these

technical terms must be researched because they are not defined in the article.

The article was designed to educate an audience that has at least a basic

knowledge of archaeology and the technical terms of that field of study.

Frere’s objective is to educate his audience on the many facts surrounding the

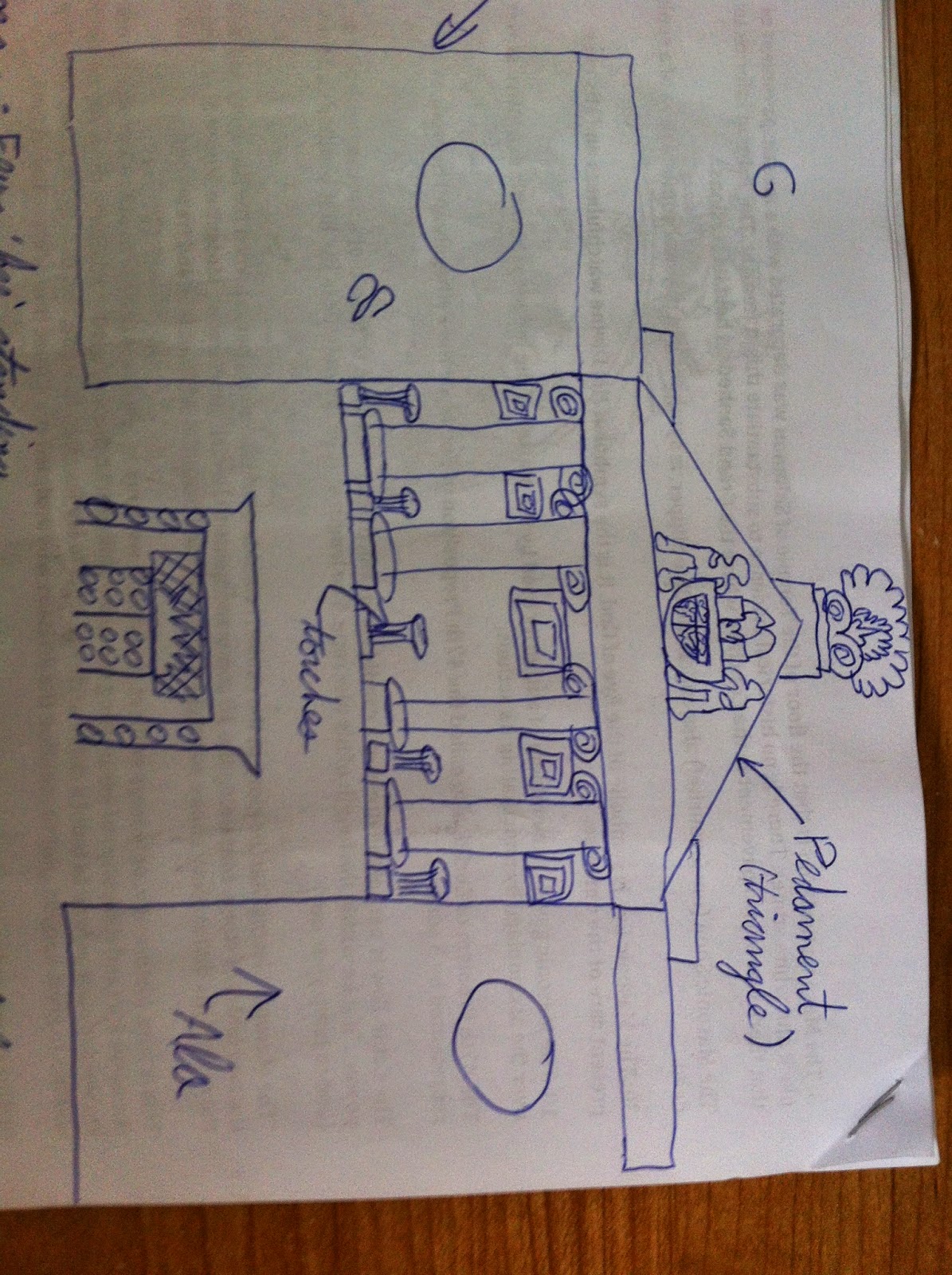

Roman theatre at Canterbury and its different components. He explains how

excavation was extremely difficult so he orientates his article less on the

process of excavation and more on the result of the dig sites. His work

includes many sketches and pictures to help communicate the main points of the

article to his audience.

Sheppard speaks about how evidence exists that the

location might have been inhabited before Emperor Claudius was in power. Objective evidence,

such as the remains of huts and their walls/plaster highlights how the area was

definitely inhabited by 60AD. The architecture of the theatre demonstrates the

style of two different periods: “The earlier building was of simple type, probably

Roman-Celtic plan” (Frere). The large curve of the cavea (seating sections)

hints towards the oval shape of an amphitheatre. Frere explains how the

different style periods of the structure are seen in the different components

of the theatre, such as walls. For example, ‘wall E’ was built earlier than

both walls ‘C’ and ‘D’. In addition, Sheppard describes how his excavations

unearthed show that ‘wall G’ was built into a trench before gravel had been added to the trench in order to help stabilize the structure. However, ‘wall D’ was “clearly laid” (Frere) into

a trench that was created by cutting into the gravel.

The theatre’s second period design is suggested to

have come during 20-210AD when the structure was “completely remodelled”

(Frere). Sheppard speaks about how certain walls of the theatre had multiple

functions. The structure was designed so that one wall (wall ‘F’) connects both

wall ‘D’ and ‘B’ together and also supported the weight of the audiences’

seats. The roman builders at the time used wall ‘A’ as a foundation, the wall

was measured at a thickness of twelve feet.

Evidence from the structural design of Canterbury’s

cathedral highlights the fact that the Roman theatre had been “built over by

1200” (Frere). By 1200AD the walls of the theatre had been degraded to the same

level as they can be found today. Sheppard theorizes that the theatre could

have been demolished under the reign of Henry I in order to build a stronghold.

However, Frere admits that Christian builders could have also been responsible

for the theatre’s destruction. This part of the article is interesting. No

concrete proof exists to ever know why the Roman theatre was destroyed and by

whom, but the demolition of the theatre highlights the end of the once mighty

Roman Empire. Evidence exists of Saxon inhabitants living in the area, but not very much.

This suggests that the structure survived the Norman conquest, but then was

quickly demolished.

Portions of the ancient Roman theatre still exist

today. As mentioned earlier, Pilbrow around 1868 discovered the first remains

of the theatre. Pilbrow sketched what is evidently the “outer perimeter wall”

(Frere). Sadly, Pilbrow did not put the exact location where this wall could be

found. In addition, the presence of several of the theatre’s old walls can be

found in underground cellars of buildings located around the area. “In the back

cellar of Slatter’s Restaurant a magnificent portion of wall A occupies a large

part of the room it seems to have been too tough for removal…” (Frere). Also,

Pilbrow’s sketches allowed for the locations of the theatre’s components to be

located using landmarks that still exist today. Supposedly, an area was

uncovered that could have been the entrance to the theatre. Unfortunately, the

remains of the ‘entrance’ had been damaged during excavation. Moreover, the

location of the ruins lies in an unstable area that stops any further examination.

Thus, confirming whether this is the ‘entrance’ to the theatre is impossible to

prove. In 1950, a “small piece of Roman wall” (Frere) was discovered under St.

Margaret’s Street. The piece of wall unearthed under St. Margaret’s was linked

to the theatre’s design from its first period. Proof suggests that the wall is

a section of the theatre’s old cavea. In 1956, trenches were dug behind an

office building located on Margaret’s Street. In these trenches a “wall and a

thick foundation of gravel were discovered” (Frere). The floor discovered with its thick gravel

foundation was unique. This uniqueness hints towards the location being “part

of the stage or stage-building” (Frere).

Fortunately, even though several artifacts were

lost or damaged throughout the centuries a few objects dating back to period I

of the theatre still exist. Objects

found in layers underneath wall E can be dated back to period I. Also, several

objects were found in the theatre that had been sealed by a gravel bank.

Artifacts around wall ‘G’ were located too. Lastly, the exaction done on St.

Margaret’s Street, 1950, led to the uncovering of more items from period I. Items

discovered belonging to period I include:

-

“Coarse granulated grey-ware bowl” (Frere)

-

“Ringed jug, granulated buff ware with near grey

core” (Frere)

-

“Samian bowl” (Frere)

-

“Wide-mouthed jar” (Frere)

-

“Bead-rim jar” (Frere)

Furthermore, objects dating back to the theatre’s second

period design were uncovered too. These objects include:

-

“Belgic jar, corrugated neck, striated body,

somewhat debased outline: neck pierced for suspension” (Frere)

-

“Bed-rim jar” (Frere)

-

“Spindle whorl made from sherd from lower side of a

striated pot; inner side scored with cross”(Frere).

-

“Belgic pedestal base, splay very bruised” (Frere)

-

“Big Belgic storage jar” (Frere)

Also, ruins were discovered outside the perimeter

walls. Evidence of a hut dating back to 60AD was unearthed. The layers under

the hut led to the finding of several artifacts. Pottery of “almost entirely

pre-Roman Belgic type” (Frere) was uncovered along with two samian sherds. Objects recovered at hut I include:

-

“Cordoned bowl, leathery brown burnished ware” (Frere)

-

“Local copy of Gallo-Belgic platter” (Frere)

-

“Roman grey ware bowl or girth beaker” (Frere)

An additional hut was found too. The pottery found

in hut II “is of brick red variety which seems to be typical of Flavian times”

(Frere). Evidence suggests that this hut was habited from 80-170/180AD. Objects

uncovered include:

-

“Storage jar in the later brick-red variety of

Belgic ware which seems to date from Flavian times” (Frere)

-

“Mortarium, cream paste, Camulodunum” (Frere)